Mapping prototypes - Cambodia scoping data

This document provides samples of maps and accompanying unstructured data (free text) presented in the DFM Cambodia Scoping Research Report.

The DFM mapping team will support the extraction of structured data from unstructured data and manually drawn maps such as these, to generate visualizations with better standards conformance usability characteristics -- including the capacity to edit, update, merge, and query geographic data.

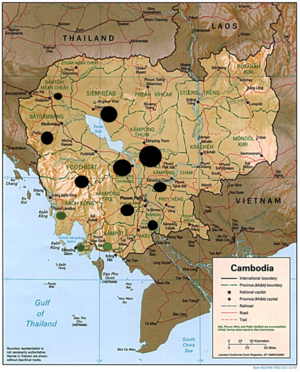

Base map

The DFM Cambodia Scoping Research Report includes several maps that are manually drawn by the author. The base map is a 1997 CIA map of Cambodia, which is freely available from Wikimedia Commons:

Ideally the map data should be redrawn on top of an OpenStreetMap base layer or similar, which will allow for rendering at different resolutions and consistent visualization of features across different countries in the region.

Points and markers

Many of the maps produced through DFM are expected to represent collections of geographic points. The map below illustrates fish processing sites in Cambodia, based on qualitative data obtained by the author through semi-structured interviews:

Current visual representation

The map was created by drawing filled circles on top of an image in a Word document, using the word processor's "shapes" tool. This approach, while accessible to a non-technical user who lacks access to GIS software, has a number of significant drawbacks:

- The marker locations (intended to represent market sites) and sizes (intended to represent the quantity of fish processed) are imprecise; many of the markers are visibly not even perfect circles due to the difficulty of manipulation of these shapes in the user interface.

- Markers are not permanently linked to the base map, so will end up in the wrong place if the map is moved or resized.

- The map as a whole cannot be repurposed outside of Word unless saved as a screenshot; exporting a high-resolution image, matching that of the base layer, is not possible without manipulating the overall document settings.

- There is no underlying dataset that can be reviewed or updated as new data become available.

- It is not possible to regenerate this map with different base or data layers, or to change the resolution (zoom level).

This map could nonetheless be used as a reference point for a dynamically generated representation. It would be necessary to work with the report author to identify and label the points on the map, establish value ranges for the different marker sizes, and associate (approximate) values with each of the markers.

Current textual representation

The accompanying textual data in the DFM Cambodia Scoping Research Report provides references to several sites that are present in the map (emphasis added):

In general, the bulk of the processing of fresh water products in Cambodia happens around the Tonle Sap (Kampong Chhnang, Pursat, Siem Reap, Battambang, Kampong Thom, Kampong Cham and Phnom Penh), to a lesser extend along the lower Mekong regions such as Kandal, Prey Veng and Takeo. Most of the previous studies have also focused on these areas. However, based on government fisheries administration data, a limited amount of processing is taking place in the upper Mekong region in Cambodia such as Steung Traeng and Kraties as well, which was not captured by the scoping phase of DFM Cambodia and had not been focused by previous studies. The coastal Provinces of Kampot, Kampong Som and Koh Kong produce marine fish based processed products, however, volume of production is smaller compared to the fresh water products (discussed below).

The text includes references to several types of features:

- Country (Cambodia)

- Lake (Tonle Sap)

- River (Mekong)

- Provinces (Kampong Chhang, Pursat, etc.), which may also in this context refer to the major cities within them that have the same name

- Regions (upper Mekong, lower Mekong)

- Analytical categories (coastal provinces) - implicitly a reference to the Gulf of Thailand

Current quantitative data representation

While the marker sizes in the above map were drawn manually, we do have access to more precise figures.

This chart is linked to a data table in an Excel spreadsheet that is embedded in the Word document (formatting added below):

| Province | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kompongcham | 7000 | 3800 | 3960 | 1237 | 1287 |

| Takeo | 5199 | 2725 | 3190 | 4563 | 3622 |

| PreyVeng | 5300 | 2945 | 3715 | 3015 | 4135 |

| Kandal | 6000 | 4575 | 6260 | 4949 | 5149 |

| PhnomPenh | 3004 | 3603 | 4460 | 4684 | 5225 |

| Porsat | 6354 | 3995 | 6965 | 6352 | 6302 |

| Batdombang | 6974 | 5120 | 6345 | 7206 | 7276 |

| Siem reap | 8035 | 6955 | 9600 | 10787 | 10857 |

| Kompongchnang | 8395 | 7385 | 11105 | 13040 | 12763 |

| Kompong Thom | 5850 | 5055 | 9250 | 13090 | 13150 |

Notably the data table provides a time series that could also be represented visually on the map. If the map is interactive, change over time could be explored using a slider, for example.

Design criteria

Ideally each of the features on the above map should be:

- labelled in the map

- linked to a legend

- associated with geographic coordinates in a GIS database, which should incorporate user-defined features in addition to commonly available coordinates and shapefiles for administrative units and the like

- linked to an online index or query engine returning references to the feature in project-generated documents (unstructured datasets including: reports, spreadsheets, QDA datasets, wiki pages)

- referenced in a simple data table and processing instructions (e.g., html form) that non-technical users can edit easily and have converted automatically into a map.

In the case of the above map we would need a minimal data table with two or three columns, indicating:

- place name (used as both label and lookup key for the coordinates database),

- volume (the size categories could be calculated with ranges supplied externally to the data table)

- label type (probably something like "processed fish", so as to distinguish between other commodities in consolidated data tables)

This information is fortunately available in the data table underlying the chart above. It would be necessary to explore design options for referencing the data most effectively in the map, in a way that minimizes potential for data entry error (copy-and-paste operations) but also allows for the underlying data table to be modified in one place as more recent data become available.

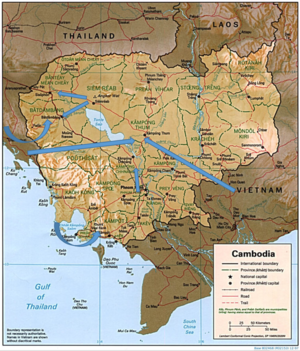

Directional flows

The second major type of geographic visualization to be developed by DFM researchers represents directional flows of fish and fish products (and potentially people as well) along value chains.

Current visual representation

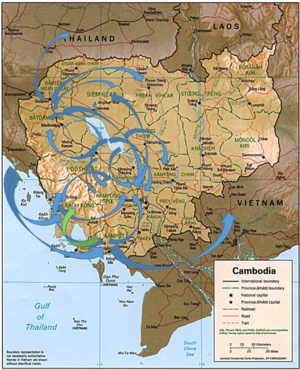

The two maps below illustrate the flows of fresh fish inputs and processed fish outputs in Cambodian dried fish value chains. Here the map elements have also been drawn using Word shapes, presenting the same limitations as seen above with the static points.

The first map illustrates the sources of fresh fish used by Cambodian processors. The source and destination points are administrative units at different levels: we have countries (Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand), but also specific sites and regions within Cambodia as processing areas (Kampung Thum, Phnom Penh, Siem Reap, etc.).

The limitations of this map are similar to those listed for the map of processing sites above. Additionally:

- The identity and scope of each source or destination point/area is not discernible from the map: is the arrow leading from Vietnam anchored to a specific market, for instance, or to the country as a whole? Although some explanatory detail is provided in the text, additional labelling or markers/polygons for source and destination points or areas could provide greater clarity.

- It would be desirable to accommodate a differentiation in volume in a future version of the map, by arrow size.

- Since all the arrows are of the same type, it is not possible to merge these two maps to create a representation of a complete value chain. Ideally arrows associated with different products, stages, or value chain actors should be differentiated by colour or some other means.

The second map indicates the destination of fish sold by processors and traders from the provincial and district markets in Cambodia. As with the map above, source and destination points correspond to a combination of town/market sites, regions, and countries.

- The green arrow appears to be an error in the map; in another map in the same document, blue and green arrows are used to differentiate between “buying routes” and “selling routes”.

- Due to the overlaps between the curved arrows, it is difficult to make visual sense of the flows of processed fish represented in this map. This problem might be less severe if the map could be viewed interactively, with flows into and out of each site being exposed as a layer that could be toggled by the user. For a static map output, we would potentially experiment with different layout algorithms, arrow sizes, and line types (straight, segmented, or curved) to minimize visual overlaps.

Current textual representation

The text accompanying the above two maps describes the "trade routes" in narrative terms (emphasis added).

The movement of processed products in Cambodia takes place at different levels: a) within the community, b) within the district, c) within the Province, d) across Districts and Provinces and f) across national borders. The two figures below are derived from primary data collected from the scoping phase and they do not include sourcing and selling routes within the Provinces and Districts.

At an extremely micro level, the scoping phase data collection came across processors who were ‘trading’ their products within their community: the floating village that they live (see case of BT PR 04 above). The majority of the processors and traders were selling their products to middlemen/Mooi, from outside the Province, or to middlemen/Mooi at the District or Provincial markets. In general, products being traded to Phnom Penh, via middlemen, was common, although trade with other fish /processed fish producing Provinces such as Siem Reap and Battambong, was also taking place, to a lesser extent. However, trade with non-fish producing Provinces such as Takeo, Prey Veng was minimal, from the Provincial and District markets. Trade between Provincial and District markets around the Tonle Sap that produce Inland water products and coastal Provinces that produce marine products were also minimal. These trade routes seem to be dominated by Phnom Penh markets, as seen from figure XX. Cross-border trade, directly from the Provinces, was not very common, except in Battambang, where the medium/large scale producers did mention trade with Thailand.

Phnom Penh markets, especially Orussey, emerge clearly as a hub for processed fish product trade in Cambodia, based on trade route mapping of District and Provincial traders and the rapid survey data of Orussey and Derm Kor markets. Products were coming to these Phnom Penh markets from both the fresh water regions around the Tonle Sap as well as the coastal regions and in turn, products were flowing from these markets out to all these regions. Orussey market also acts as a gateway between fresh water regions and products, and coastal regions and marine products, as products pass through the market, probably based on its geographic location and established transport and logistics networks.

As explained above, Cambodians living abroad, or those visiting their relatives living abroad and to a lesser extent foreign visitors, also formed an important customer base for these products from the Phnom Penh markets. Another trade route extends to Vietnam and Thailand, primarily via middlemen, both Cambodian and non-Cambodians.

The text describes four different types of trade, which ideally should be represented distinctly in the map data. There is reference to several specific markets and mobile "floating villages", all of which would need to be added manually to the GIS coordinates database. Additionally, the text refers to "coastal" and "freshwater" regions and provinces, which could be identified on the map.

The trajectories to diaspora consumers and to neighbouring countries (Vietnam and Thailand) are less well documented, but also more dispersed. Alternatives to directional arrows might be appropriate in these cases.

Design criteria

The design criteria for the directional flow maps are mostly the same as for point/marker maps.

In these instances we would need a minimal data table indicating:

- source place name

- destination place name

- approximate volume of trade

- commodity type

In this instance we do not have access to quantitative data; evidence of trade routes is extracted from a small sample of semi-structured interviews with fish traders and processors. Consequently, the trade volumes need to be designated manually based on estimated relative categories (e.g., "minimal", "moderate", "high").

Some quantitative data on trade volumes will be collected through surveys in the next stage of the DFM project, but not for all regions. It will be helpful to anticipate connecting data on trade volumes from various data sources having different levels of precision.