DFM Sri Lanka literature review - Dried fish consumption

With 83% of the population professing a Buddhist or Hindu religious affiliation, there is a strong cultural preference for fish over other animal protein sources in Sri Lanka [1]. Sri Lankans prefer fish to meat, which is evident from Figure 7.1 and Figure 7.2, where the consumption of fish shows a continuous increase from 2006 to 2016. Fish remains by far the highest consumed meat or fish product by households (Figure 7.1), with fresh and dried fish together amounting to 2.5 times over the monthly average consumption of all other meat products combined in 2016. While fresh fish consumption has remained relatively constant during 2006-2016, chicken has gradually overtaken dried fish by 2012, to become the second-highest consumed meat and fish product by households after fresh fish. Figure 7.1 also shows a declining trend in dried fish consumption from 2006, decreasing from second to third place in 2012. The gap between chicken and dried fish consumption has widened from 2012 onwards. However, dried fish consumption remained at an important third place in 2016.

There is a lack of research on the cultural preferences for meat consumption in Sri Lanka and why fish or chicken might be preferred over other meats. Religious taboos prevalent for the four religions practiced in the country – Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam and Christianity – as well as regional preferences would need to be explored to understand these changes within the consumption segment of the value chain.

The average monthly consumption of dried fish per household was about 1.1 kg, whereas fresh fish consumption was 4.1 kg in 2016 [2]. Thus, there was a threefold demand for fresh fish over dried fish. However, if the conversion of dried fish into the wet weight were taken into account, dried fish consumption would represent at least the equivalent of wet fish, both in terms of quantity and nutritional value. The same pattern is noticeable at the individual level, where fresh fish consumption far outpaced meat and meat-related products, followed by chicken and dried fish (Figure 7.2). However, it is important to note that the monthly dried fish consumption per capita declined during 2009-2012 to rise however, to 2009 levels by 2016, not consistent with the level of gradual decline in average household consumption. This might be due to the decrease in average household size (from 4.0 to 3.8) during this period [3].

Despite the quantity of dried fish consumption in grams per month at the household level showing a decreasing trend and the quantity of chicken consumption showing an increasing trend from 2006 (Figure 7.1), the expenditure on dried fish consumption has gradually increased in the same period at a slightly higher gradient than chicken consumption (Figure 7.3).

On average, households in Sri Lanka spent 2.4 times more on fresh fish than dried fish in 2016 (Figure 7.3). In comparison, with the quantity - three times more fresh fish than dried fish consumed by households in 2016 (calculated from Figure 7.1) – the difference in the expenditure ratio indicates relatively higher marginal expenditure on dried fish (Figure 7.6). This is further validated by the percentage share of monthly expenditure on fresh fish, which is 2.4 times more than dried fish (Figure 7.4).

The declining percentage share of expenditure on dried fish seems to be captured by the increasing percentage share of expenditure on chicken (Figure 7.4). The percentage share of expenditure on dried fish declined gradually from 2002 to 2006, reaching a plateau until 2012. On the other hand, the share of expenditure on chicken decreased slightly from 2002 to 2006 but increased thereafter, reaching near parity with the dried fish share in 2016.

The changes in average household expenditure on dried fish and chicken are consistent with the price effects of chicken over dried fish. Price variation of the main three dried fish varieties consumed – skipjack tuna (balaya), sprat (anchovy), and queen fish (katta) – was analyzed in relation to chicken prices (Figure 7.5). Although the price of chicken was relatively constant from 2009 to 2016, the prices of skipjack tuna and queen fish have increased markedly with a higher gradient. However, sprat prices do not show as high an increase as the other two dried fish varieties, reaching 1.5 times the price of chicken in 2016, whereas skipjack tuna and queen fish show 2.12- and 2.75-fold prices respectively, relative to chicken prices in the same year.

The relationship between the expenditure in purchasing a kilogram of dried fish relative to a kilogram of chicken is shown in Figure 7.6. A kilogram of dried fish was 1.4 times the price of chicken for a household in 2016. It needs to be noted that if the conversion from dry weight to wet weight of dried fish were considered, the nutritional value of a kilogram of dried fish would be considered higher than a kilogram of wet chicken.

However, the proportion of monthly average expenditure of households on dried fish, compared to that of other animal protein to the food basket, has remained relatively constant from 3.5 percent in 1980/81 to 4 percent in 2016. In contrast, the proportion of household expenditure on fresh fish towards the food basket rose from 5 percent to 9.5 percent, while the proportion on chicken rose from 1.8 percent to 3.75 percent in the same period, indicating higher increases in expenditure shares on these other animal products in households.

When countrywide household monthly expenditure on dried fish is disaggregated by three sectors (urban, rural and estate), based on geographical, demographic and socio-economic characteristics in Sri Lanka, rural households show the highest expenditure, followed by those of the urban and estate sectors respectively (Figure 7.8). Rural households have been spending more than urban and estate households consistently since 2005 and spent around 1.8 times more on dried fish than estate households in 2016.

Lokuge et al. [4], in their discussion of household food consumption and demand for nutrients, state that urban households are less likely to consume dried fish than rural households (as confirmed in Figure 7.8), and estate households more likely to consume dried fish than rural households (unconfirmed by the current consumption data). They point out that while all animal proteins are price elastic in Sri Lanka, dried fish is less price elastic and can be considered as a substitute for more costly animal source food, such as meat and eggs. The protein intake of households can be affected by price variations in both fish and dried fish. Lower sensitivity to price changes in dried fish, as for cereals, vegetables, and coconut, indicates it as one of the most important food groups in the Sri Lankan diet, for cultural and nutrition reasons. In addition to protein, dried fish is also important as a source of micro-nutrients, unavailable in other meat products.

As data on expenditure on total dried fish consumed in relation to expenditure deciles were not available at the national level, HIES data [5] on the share of average monthly household expenditure on the two main dried fish varieties (skipjack tuna and sprats) consumed as a proportion of a total of five selected animal food items (chicken, beef, fresh skipjack tuna, fresh sailfish, dried skipjack tuna, dried sprats) for which data were available in relation to expenditure deciles, were analyzed. This showed an inverse relationship between expenditure decile and dried fish expenditure. Lower expenditure deciles have a higher share of expenditure on dried fish and vice versa (Figure 7.9). The proportion of dried fish expenditure to other selected animal food items was especially high at 50% and 37% for the two lowest deciles respectively, revealing the significant role played by dried fish, as an animal protein, in the diet of the poorest households in Sri Lanka.

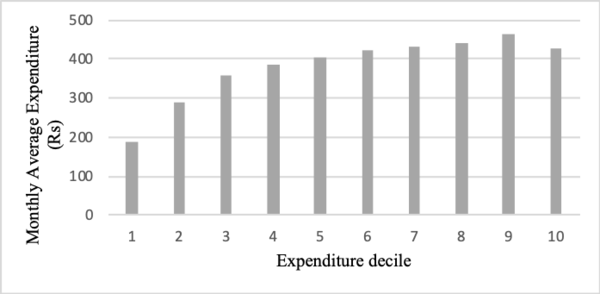

However, the absolute expenditure on dried fish by expenditure decile reveal an increasing trend by decile with households in the higher deciles spending considerably more on dried fish on average per month than the lower deciles. The ninth decile (which revealed the highest monthly average household consumption) spent 2.5 times more than the lowest decile on dried fish on average per month.

An analysis of the geographical variation in average monthly household expenditure on dried fish reveals that households in Kurunegala (interior), Gampaha (coastal), Kegalle (interior) and Galle (coastal) districts, in that order, spent the most on dried fish consumption in 2016 (Figure 7.10). The lowest expenditure was recorded from Jaffna (coastal), Kilinochchi (coastal), Vavuniya (interior), and Mannar (coastal) districts, in that order, in the same period (Figure 7.10). Household expenditure on dried fish has increased between 2006/2007 and 2016 in all districts, consistent with the increase in expenditure on dried fish at the national level during the same period.

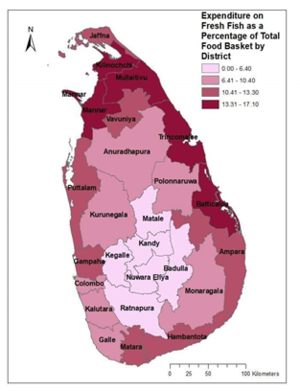

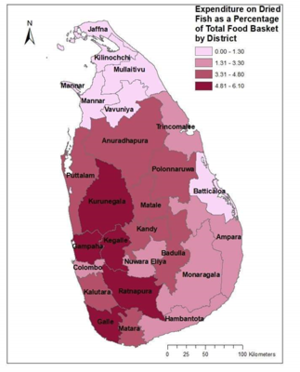

An analysis of the share of the quantity of fresh fish consumed monthly on average by a household of a food basket comprising the main food groups in Sri Lanka reveals that most coastal districts (with the exception of those on the west coast) consumed more fresh fish than interior districts, with the highest proportion in coastal districts of the north and east. The consumption of dried fish reveals a different pattern. The highest share of dried fish consumption from the same food basket is revealed in the western, north-western, and north-central interior districts of the country, as well as the western and southern coastal districts. The share of dried fish consumed is lowest in the northern and eastern coastal districts, as well as the south-eastern interior districts. Thus, coastal districts with the highest expenditure on fresh fish consumption in the North and East show the lowest expenditure on dried fish consumption. This mapping reveals that there are regional preferences for fresh and dried fish, that might not correlate with national price analysis.

Furthermore, despite the higher price of dried fish in relation to meat, which is determined by the chicken price, as the most consumed meat, there are several districts in Sri Lanka with households allocating a higher proportion of their food basket to dried fish over meat, revealing regional and/or socio-cultural preferences for dried fish over meat. As Figure 7.11 shows, these districts are: Kurunegala, Kegalle, Galle, Ratnapura, Polonnaruwa, Kalutara, Badulla, and Matara, three of which are coastal and five of which are interior districts. Four of these districts, Kurunegala, Kegalle, Galle and Kalutara are also among the five top districts showing the highest overall average monthly consumption expenditure on dried fish of households in the island. The reasons for the preference for dried fish in these districts, and the extent of the significance of socio-cultural factors (e.g., the majority of the population of these seven districts are Buddhist) could be explored by the study.

In assessing demand for different varieties of dried fish, national-level data reveal that sprats (anchovy) are by far the most consumed, followed by Skipjack tuna, shark, and Smooth belly sardines.

| Dried fish | 2006 | 2009 | 2012 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sprats | 590.12 | 556.44 | 500.22 | 487 |

| Smoothbelly sardines | 82.31 | 69.46 | 93.18 | 76.41 |

| Sardines | 45.96 | 48.52 | 47.99 | 43.69 |

| Spotted sardinella | 38.2 | 34.36 | 41.4 | 22.85 |

| Seer | 8.52 | 5.74 | 4.25 | 4.14 |

| Talang queen fish | 71.49 | 78.43 | 74.8 | 74.82 |

| Koduwa | 1.73 | 1.94 | 2.58 | 1.51 |

| Anjila | 0.59 | 0.83 | 1.41 | 2.46 |

| Skipjack tuna | 188.57 | 140.24 | 111.42 | 113.15 |

| Shark | 85.14 | 93.93 | 79.74 | 84.19 |

| Dried fish | 2006 | 2009 | 2012 | 2016 |

| Trevally | 8.15 | 6.58 | 6.31 | 5.75 |

| Anguluwa | 57.42 | 69.48 | 54.07 | 41.23 |

| Prawns | 8.47 | 8.99 | 6.71 | 9.16 |

| Cuttle fish | 0.73 | 1.29 | 0.94 | 1.26 |

| Fresh water dried fishes | 22.37 | 17.97 | 17.38 | 14.68 |

| Jaadi | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.95 | 0.42 |

| Other dried fishes | 113.17 | 120.76 | 99.03 | 113.55 |

(Source: DCS 2006; 2009; 2012; 2016)

Average monthly household expenditure on dried fish varieties also follows the same pattern, indicating the highest amount being spent on sprats, followed by Skipjack tuna, shark and Smooth belly sardines. The external trade figures discussed previously confirm this high preference for sprats (anchovy) by Sri Lankan households. However, no data are available on whether these patterns of demand for specific varieties persist within the districts as well.

Data on the consumption segment of the dried fish value chain are quite comprehensive at the national level. However, these macro-level statistics and data analyzed so far do not provide an adequate picture of regional variation, ethnic, gender or local preferences in consumption. Jayantha and Hideki [6], who assessed post-tsunami seafood consumption in Sri Lanka, found that that the breakdown of fresh fish consumption was 45% large marine fish, 38% small marine fish, 16% freshwater and 1% aquaculture fish. Fresh fish consumption depended on the income level and the region. The upper and middle classes consumed high value large pelagic species, such as Spanish mackerel (seer), Yellowfin tuna, skipjack tuna, and shrimp, whereas the lower classes consumed low-value small species such as reef fish and shore seine varieties (ibid.). Southern consumers' preferred large pelagic species (so-called “blood fish”), and northern and eastern consumers opted for reef fish and shore seine varieties (ibid.). Consumers in urban cities, such as Colombo, preferred white fish, such as Spanish mackerel and trevally. No research is available to show whether dried fish consumption follows a similar or different pattern. A small study [7] carried out in three Divisional Secretariat (DS) divisions in Trincomalee district (Kinniya, Trincomalee town and Gravets, and Kuchaveli), which has a multi-ethnic population, reveals that common dried fish varieties consumed are queen fish (Khuronemus) (28%), sprats (Anchovy spp) (25%), Skipjack tuna (Thunnus albacores) (25%), sardinella (Amplicaster spp), and Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus cavalla). Queen fish (Katta), a bony fish, is most popular because the dried form is considered tastier than the fresh form. Consumer purchasing decisions are dependent on the appearance, colour, and smell of the commodity. Highly fluctuating prices (77%), lack of availability (22%), and poor quality (10%) were stated as constraints encountered by the sample of respondents [8]. There is a need for more studies of this kind.

| Dried fish | 2006 | 2009 | 2012 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sprats | 127.14 | 184.62 | 246.96 | 296.04 |

| Smoothbelly sardines | 23.78 | 27.49 | 51.22 | 50.37 |

| Sardines | 9.07 | 13.01 | 17.79 | 18.04 |

| Spotted sardinella | 7.42 | 10.38 | 17.89 | 12.23 |

| Seer | 2.86 | 3.69 | 3.88 | 3.97 |

| Talang queen fish | 29 | 49.89 | 66.46 | 75.43 |

| Koduwa | 0.42 | 0.78 | 1.72 | 1.07 |

| Anjila | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.75 | 1.47 |

| Skipjack tuna | 50.58 | 62.32 | 70.12 | 84.31 |

| Dried fish | 2006 | 2009 | 2012 | 2016 |

| Shark | 26.25 | 47.77 | 58.3 | 75.42 |

| Trevally | 3.1 | 3.02 | 3.92 | 4.22 |

| Anguluwa | 13.6 | 24.86 | 28.36 | 29.44 |

| Prawns | 2.54 | 4.48 | 4.8 | 7.37 |

| Cuttle fish | 0.17 | 0.51 | 0.5 | 0.88 |

| Fresh water dried fish | 6.16 | 8.04 | 9.19 | 8.43 |

| Jaadi | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.45 | 0.29 |

| Other dried fish | 31.75 | 51.02 | 57.31 | 78.18 |

(Source: DCS 2006; 2009; 2012; 2016)

There are a variety of preparations of dried fish- as curries in coconut sauce, deep-fried, stir-fried, pickled - which are part of the cuisine of different ethnic groups in Sri Lanka. Very little research is available on the culinary diversity of dried fish. There are thousands of Sri Lankan dried fish recipes circulating on the internet, including many videos, which might provide data for an analysis of the regional and ethnic diversity in the preparation of dried fish.

An additional area of inquiry is the symbolic importance of dried fish in Sri Lankan culture. For example, the main funeral meal (malabatha) among the Sinhalese ethnic group in the Colombo region is rice accompanied by a dried fish curry cooked in a coconut sauce (karawala hodi), pumpkin and ash plantains. There does not seem to be any published ethnographic work on funeral rituals, which explores the symbolic relevance of dried fish in ritual food in Sri Lanka.

Thus, the macro-level sources provide a wealth of data on national and regional dried fish consumption patterns in Sri Lanka. However, there is an enormous gap in the literature on preferences for dried fish varieties by ethnic, religious and gender group, local variations in culinary use and taste, and symbolic significance in Sri Lankan culture.

- ↑ Jayantha and Hideki, “An Analysis of the Post Tsunami Domestic Fish Marketing and Consumption Trends in Sri Lanka”.

- ↑ DCS, “Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2016”.

- ↑ MFARD, “Fisheries Statistics 2018”.

- ↑ Lokuge Dona et al., “Household Food Consumption And Demand For Nutrients In Sri Lanka”.

- ↑ DCS, “Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2016”.

- ↑ Jayantha and Hideki, “An Analysis of the Post Tsunami Domestic Fish Marketing and Consumption Trends in Sri Lanka”.

- ↑ Krishnal and Dayaani, “Behavior of Household Dry Fish Consumption in Trincomalee District”.

- ↑ Krishnal and Dayaani, “Behavior of Household Dry Fish Consumption in Trincomalee District”.