Karnataka weights and measures study

Amalendu Jyotishi, Prashanth R, Prasanna Surathkal, Ramachandra Bhatta, Holly M. Hapke, Nikita Gopal

Introduction

Unit-based pricing (e.g., price per piece) and weight-based pricing (e.g., price per kg), are two of the most common pricing strategies for unpackaged groceries in modern retailing business. Dried fish markets of Karnataka (Uttara Kannada district in particular), mostly run by women, show how they navigate traditional weights and measurements on the one hand and prices on the other that vary by fish across the supply chain nodes. While mapping the dried fish markets in Karnataka, the authors noticed that sellers of dried fish use different weights and measurements for selling different fish species. We probed further in the supply chain to understand what measurements are followed in the procurement process of different species. This led us to multiple and varied measurements in various nodes of the supply chain of different species. We found some species being sold in counts/numbers (unit-based pricing), some in kgs (weight-based pricing), some by non-standardized heaps, and yet others by volume measured in Kolaga and Seru- two pails of different sizes for measurement. To add to the complexities, the weight of the fish (in terms of mass and volume) goes through a change as the wet fish loses weight in the drying process and level of moisture content. The amount of salting would also change the weights. This led us to ask, how do the women-small-scale dried fish processors and traders navigate varied weights and measurements used during procurement, processing and selling the products to the consumers? How do experience and intuitive cognitive abilities help these women who are barely literate, to navigate the process? Is there a trade secret from which they tend to gain, or do they lose out or discount their own (non-market and mostly labor) contribution in the process? Why don’t they follow a uniform method of measurement across the species and in the supply chain? Are there patterns associated with such weights and measurement practices? For example, do different patterns of measurements explain anything about the local food system? Do homogenization and standardization of units and measurements then become a part of long-distance trading and transactions?

Through four short case studies we explain the process of measurement in different nodes of the dried fish supply chain. While we group some species across different types of measurement in the supply chain, we also follow a few species, in an attempt to understand and document such varied measurement practices. To address a larger question, homogenization and standardization of measurement is one of the prime attributes of a capitalist economy and its expansion. In that context, we can raise questions about how multiple economic systems of transactions co-exist and what such transactions tell us about the economic system, which is perhaps embedded in localized, social, cultural, and path-dependent practices.

Weights and measurements are fundamental elements for transactions in product markets, and these have evolved over time. Traditional weights and measurements are often highly localized. They are found in transactions of various commodities including food and many other essential items. Such practices also change over time driven by numerous factors. The Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka was once known for its traditional fishing, but as time passed, mechanization and motorization of fishing crafts increased, though the district still has substantially larger share of non-motorized boats compared to the other two coastal districts of Karnataka.[1] However, traditional weights and measurements are being used even today at various stages in the fisheries sector of the district, majorly in the dried fish business. In 1790, scientists from all across the world began to embrace and use the International System of Units. More than two centuries have passed since then, yet old weights and measurements may still be found in some areas, which is both culturally and economically fascinating. This type of traditional weights and measurements can be seen more prominently in Uttara Kannada's dried fish markets. For example, dried mackerel is typically sold by the counts; croakers and Lactarius (False Trevally) in baskets; and shrimps and tiny fish like anchovies in bowls. To understand the use of different weights and measurements along the supply chain of these individual dried fish products, we observed the transactions made by dried fish processors and retailers through a case study approach. Figure 1 shows the fish species chosen for the case studies. These fish are: the Indian mackerel (Rastrelliger kanagurta); False Trevally (Lactarius lactarius); anchovy (Stolephorus commersonii); and the Indian white shrimp (Fenneropenaeus indicus).[2]

Case Studies

Weights and measurements in the dried Indian mackerel supply chain

The Indian mackerel (Bangudey/Bangda in Kannada and Tulu) has long been regarded as one of the most valuable dried fish. Karnataka is considered the mackerel coast due to the large catches of mackerel during peak fishing seasons. It is the fisherwomen who are in charge of the fish-curing and drying operations, and fish processing and marketing in general. Fisherwomen in Karwar's Tagore Beach, Baithkol, and Majali areas have been producing dry-cured fish for generations. Retail customers come here even from the neighbouring Goa state to purchase dried fish, particularly mackerel. Particularly in Uttara Kannada fishing and fish marketing are integrated in the family in the sense that the husband goes out to fish and gives the harvest to his wife. The wife decides what amount to retain for home consumption, what to sell in retail markets as fresh fish, and processes the fish further (primarily by salting and drying) for selling in the retail market. Thus, women take care of the financial and physical transactions of the fish business. Fisherwomen typically use the unsold wet mackerel (one or two days old fresh/raw fish unsold in the market) for drying and curing. The fish are rinsed with water and dried in the sun. This process results in high-quality dried mackerel. However, processing a small quantity of unsold fish into dried fish is not economically viable. As a result, the processors involved in the dried fish processing rely on various additional sources for the raw materials. These sources include agents who collect unsold mackerel from various wet markets and from various landing locations, straight from the boats, through auctions, and so on.

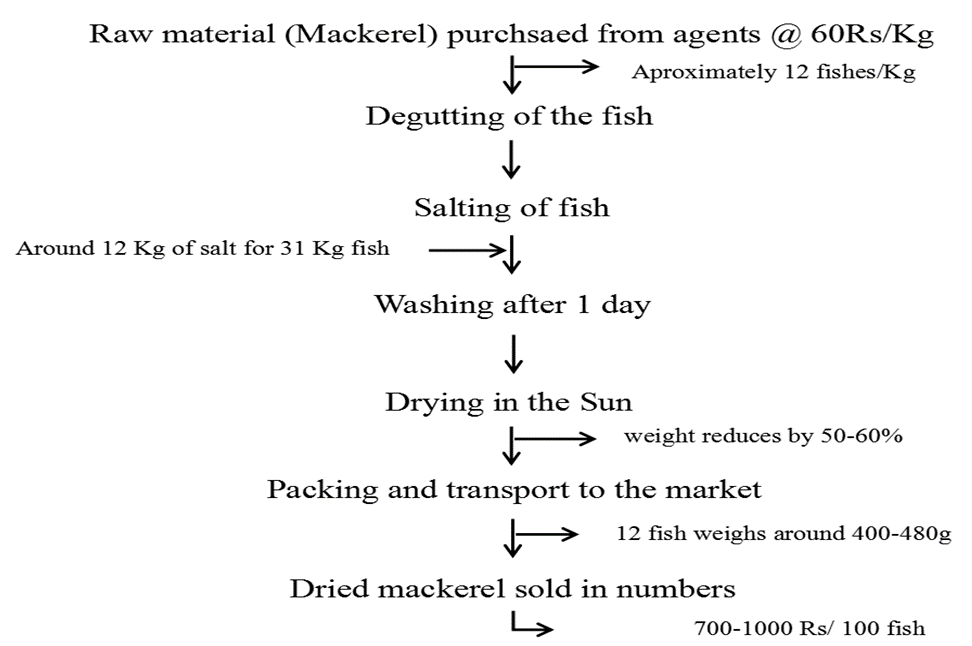

One of the women processers, Sharada (name changed), discussed the method she uses in the processing and the weights and measurements she uses in trade. She is a fisher woman who produces dried mackerel near Tagore Beach. She has no family members who practice fishing. As a result, she is dependent on the agents who bring the mackerel from various places, and she purchases it in kgs. She sells dried mackerel in numbers (count system) at the Sunday wholesale market. The entire supply chain is shown in Figure 2.

Figure . Weights, measurements and prices in the dried Indian mackerel supply chain.

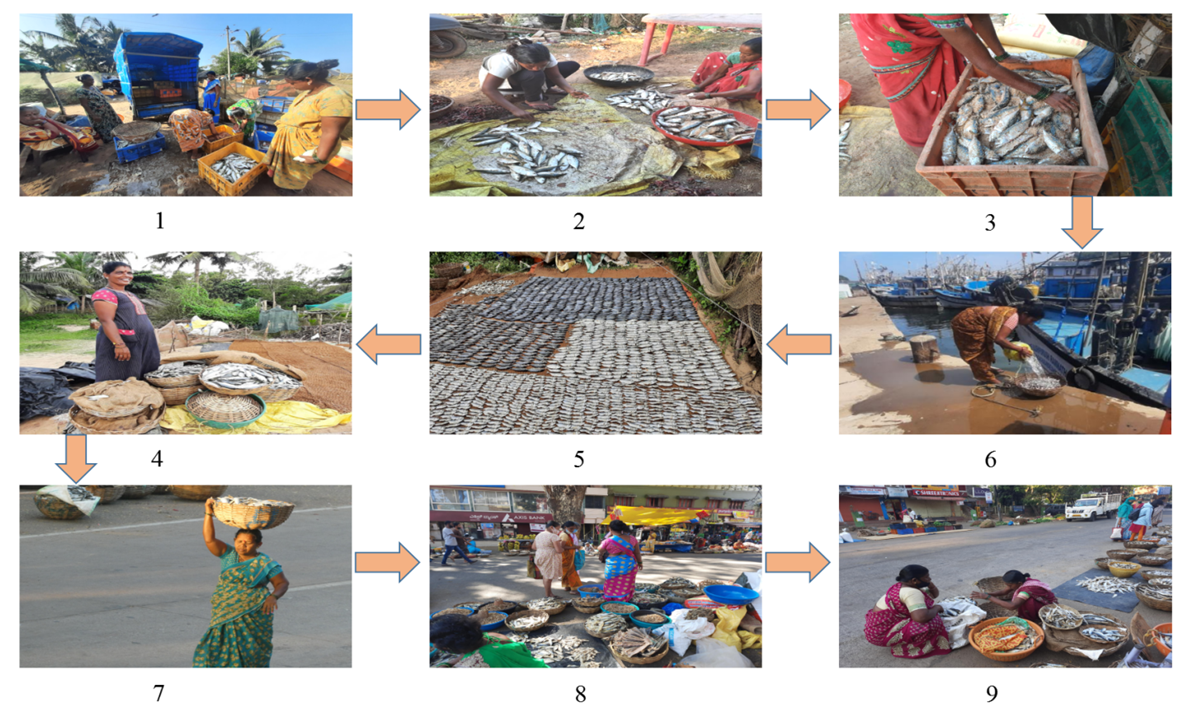

Table 1 shows the weights and measurements used in typical mackerel dried fish supply chain in Uttara Kannada. These data are collected from Sharada. Sharada paid 60 rupees (₹) per kg of mackerel. It was a medium size fish, and a kg of mackerel contained 12 counts of fish. Each box of fish weighed around 31kg. She removed the mackerel's gut and gills, a process called degutting/gutting. The fish belly is then stuffed with salt and stored in a box for 1 to 2 days. Following that, the salted fish is rinsed in water to remove excess salt content. The washed fish is spread out on a coconut coir mat, encircled by an abandoned fishing net. It takes two sunny days for the fish to dry to the appropriate level. The dried fish in the process loses 50-60% of its moisture content. The same 12 dried mackerel that weighed one kg would now weigh 400-480 grams. The dried mackerel is then packed in bamboo baskets and carried on head to the nearest weekly market, known as the Sunday Bazar. It was sold there for rupees 800-1000 for every 100 counts of dried mackerel. She processes and sells 4 to 6 baskets/boxes of mackerel every week based on raw material availability. Figure 3 provides a photographic coverage of different stages in dried mackerel processing and the weights and measurements used therein.

Table 1. Weights, measurements and prices along the dried mackerel supply chain at Karwar.

| Dried fish supply chain stage | Weights and measurements used | Amount | |

| Raw material (wet fish) procurement | 31 kg mackerel per basket;

About 12 fish per kg of mackerel |

₹60/kg fish,

12 fish×31 | |

| Salting | 12 kg for 31 kg fish | 12×₹5 = ₹60 | |

| Transportation cost | Nill (headload) | ||

| Weight reduction by 50-60% | 12.5 to 15 kg dried fish yield | ₹2976-₹3720 | |

| Selling price at Karwar wholesale market | Sold in counts of 50, 100, 200, 1000. | ₹8-₹10 per fish | |

Sharada procured three boxes of mackerel in the first week of October 2021, through the agents at wet fish markets in Karwar, Hubballi, and Goa. The fresh fish are usually sourced from the Baithkol landing centre, but they went unsold in the destination/retail market. The agents who supply wet fish to retail markets collected back the unsold fish. They purchased in kgs and in lots depending on the quality of the fish. People in Karwar and Goa emphasize on the freshness of the fish. Therefore, fishes are graded on quality (freshness). Demand for lower quality fish is quite low. Fish stored in cold storage for an extended period of time are considered as poor-quality fishes and are used in dried fish processing.

Sharada’s story is a general case of numerous little variations across the Karnataka coast in relation to mackerel weights and measurements in different supply chain nodes. At Bengre in Mangaluru raw material for dried fish production is obtained in kg, either straight from the boat or from an agent. The agents were able to obtain mackerel suitable for dried fish processing from multiple vessels in tiny quantities at various prices. Then it sells to the producers in baskets (20- 40 kg) at a price determined by the weight of the product. The dried fish is sold in two varying volume baskets at the Mangaluru wholesale market, each holding roughly 20 and 40 kg of fish. The cost is determined based on the weights contained in the baskets. In Gangolli, Kundapura, the raw material for dried mackerel is obtained from boat agents. The agents buy a large quantity of fish from the boat. The agent’s experience allows her/him to estimate the weight of the fish. Then s/he gives it to the processors, using kg as the unit of measure. The raw material is purchased in baskets (30-40 kg) at a price dependent on the weight of the fish. After the mackerel has been dried, it is sold by the kgs to customers from all across the hinterland and coastal lands.

Processors like Sharada purchase fresh mackerel in kg and then sell the product in counts defying the modern standardized unit system. This count system is also being used by retailers. It is particularly common in the Uttara Kannada district's dried fish sector. Most of these processors engaged in dried fish processing are small in scale. They put substantial time and labour to earn their livelihood. This weights and measurements system has helped local processors make a reasonable return on dried mackerel fish as we will see in table 5 and 6.

Weights and measurements in the dried Lactarius (False Trevally) supply chain

Lactarius (Adey meenu in Kannada/Tulu) is considered one of the delicacies among the dried fish varieties available. It is produced by nearly every dried fish processor along the coast. This species is in greater demand among dried fish retailers in the hinterland. We observed the Lactarius dried fish operations at Tadadi in Uttar Kannada district. During the months of September to March, the fishing boats at the landing centre bring huge harvests of this fish and the processors buy it directly from the boats or through auctions. Apart from Tadadi landing centre, the raw material comes from Mangaluru and Malpe, and the local agents bring it to the processors here.

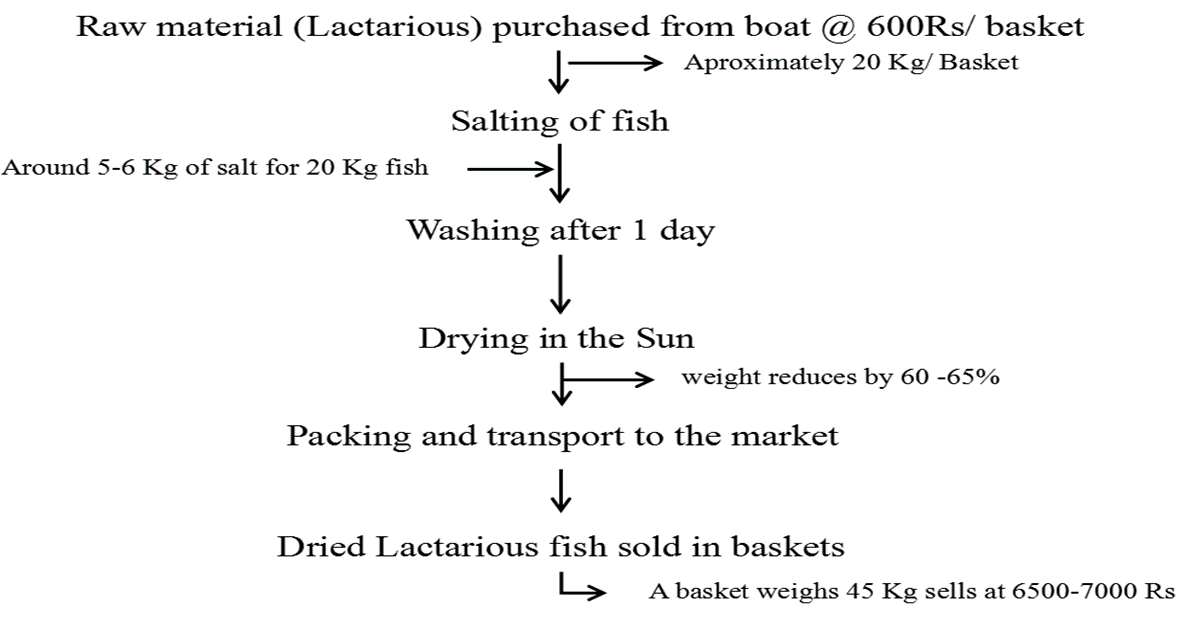

Shakuntala (name changed), one of the women dried-fish processors, spoke about the method she employs to navigate various weights and measurements in the supply chain. She buys the raw materials straight from the boat and at times through a local agent. Shakuntala processes fish by adding salt after acquiring raw material from the boat or the agent. She uses 4-5 kgs of salt per basket (approximately weighing 20 kgs) of fish. She keeps the fish for one day in a plastic container. She then rinses the fish in the Aghanashini estuary water to remove any excess salt. The fish is kept in a tiny basket to allow the excess water to drain. She then scatters it on a cement platform that she leased for a year. The fish need 1 to 2 days to dry. In the process, it losses 60-65% of weight. Fish processed in this way is regarded as ‘ideal quality’ by buyers. She arranges the dried fish in a basket to contain about 45 kilograms of Lactarius. She carries the fish, using locally available transportation (most often private transport) to the wholesale markets in Ankola or Karwar, where she sells the entire basket or fragments of it.

Figure . Weights, measurements and prices in the dried Lactarius supply chain at Tadadi.

Table 2 shows the weights and measurements at different stages of Lactarius production and the corresponding prices received. Sharada wants to sell the entire basket for ₹6500 to ₹7000, which would give her a return of roughly ₹150/kg of dried Lactarius. The retailers, particularly head-loaders and hinterland sellers, sell dried Lactarius in smaller heaps or piled in smaller baskets. Each basket or stack of fish weighs roughly 390 grams and is sold for 100 rupees. This gives them a return of ₹257/kg. The selling weight varies from one retailer to another. The size of the heap is determined by a variety of factors such as purchase price, shipping cost, weight loss, land fee for setting a shop, size and perceived quality of the fish and so on. Typically, in the Karwar retail shops, they quote a base price of ₹150 and then sell it for ₹100 after a process of bargaining and negotiation. A retailer in the hinterland, such as Shirasi sells 250g of Lactarius for ₹100. This results in getting a return of ₹400/kg of dried fish. Figure 5 provides a photographic coverage of different stages in dried mackerel processing and the weights and measurements used therein.

Table . Weights, measurements and prices along the dried Lactarius supply chain at Tadadi.

| Dried fish supply chain stage | Weights and measurements used | Amount |

| Purchasing the raw material (fish) | 20 kg basket of Lactarius×6 baskets | ₹600 × 6 = ₹3600 |

| Salt per basket | 5 kg for 20 kg fish ×6 baskets | 5×20×₹4 = ₹400 |

| Transportation cost | 150 per basket | ₹150 |

| Weight reduction by 60-65% | 7-8 kg yield from 20 kg ×6 baskets | 45 kg |

| Selling price at Karwar wholesale market | A basket of 45 kg of fish | ₹6500-₹7000 |

The processors buy raw/wet Lactarius in baskets and sell dried Lactarius in baskets and heaps, but the conversion into weights (kg) is taking place in the background. Uttara Kannada processors, in comparison to Dakshina Kannada and Udupi processors, are small-scale processors that do their own processing and marketing. If they sell the fish in kg in the wholesale market buyers are likely to converge on the lowest price offered by the vendors or negotiate for the lowest price offered in the market. A heap of 390g costs ₹100 at the retail market. The processor would make ₹250-260 if she sold 1 kg of fish. Thus, selling by the heaps gives better returns than selling by the weight. For different processors, the cost of processing and labor varies. This could be one of the stronger reasons why the processor continues to sell dried fish in heaps and baskets. This method helps them to realise a reasonable return on their cost of production to earn a decent livelihood.

Of course, there are slight variations across regions in the working of the dried Lactarius markets. In Mangaluru, raw material is purchased in kgs, either directly from the boat or through an agent. The dried Lactarius that has been processed is also sold in kg at the local wholesale shop. At Kundapura, raw material is obtained in a basket (30 kg weight) and processed dried fish is sold in kg to the customers mostly coming from the hinterland of Karnataka. This seems to suggest that the longer the chain, the more profitable it is to sellers near the end to sell in heaps.

Weights and measurements in the dried Anchovies supply chain

Anchovy is a highly sought-after, nutrient-dense small pelagic fish consumed in Karnataka coast and elsewhere. There are various species of anchovies caught along the Karnataka coast. Anchovies, including Stolephorus commersonii, are commonly called Kollatharu in Kannada/Tulu, while the Golden anchovy or the Gold-spotted grenadier anchovy (Coilia dussumieri) is called Mandeli. A significant proportion of anchovies are used for dried fish processing. The dried anchovies are used for consumption by coastal fishing families especially during the rainy season when fresh fish availability is relatively less. As a result, almost every processor compulsorily makes dried anchovies. During the fishing season, when anchovies are available in abundance, medium and large-scale processors especially favour producing dried anchovies. Depending on the salt-to-fish ratio, it may be made into several types of dried fish. As a result, the price is determined by the amount of salt in it. Low-salt-content fish is expensive compared to high-salt-content fish in the Karnataka coast.

Honnavara fishing harbor is one of the largest fish landing facilities in Uttara Kannada. Anchovies are landed from September to May, with the peak fishing season in Honnavara being January to March. The raw fish are purchased by the processors either directly from the boat or through the agents. The raw material is also supplied by the agents from Kundapura and Bhatkala landing centres.

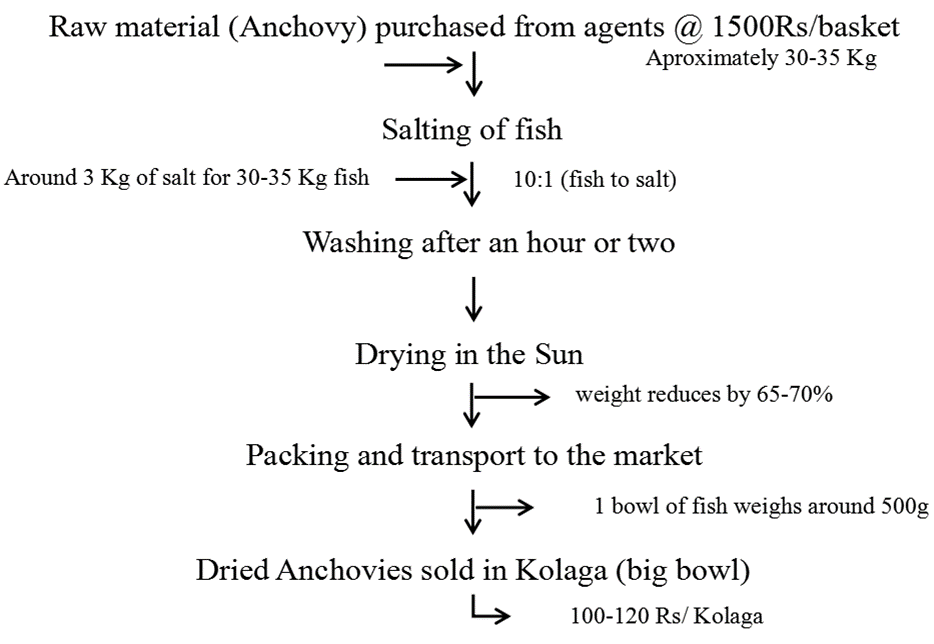

We spoke to Roshan Begam (name changed) at Honnavara, a veteran of the dried fish business for last 35 years about the dried anchovy procurement, processing and the weights and measurements used in the supply chain. Figure 6 shows the weights and measurements used at different stages of supply chain of dried anchovies and the prices. Roshan Begam obtains the raw material directly from the boat. She buys the raw material in baskets that weigh between 30 and 35 kg and costs roughly ₹1500. She adds salt to it in a cement tank in a 10:1 (fish to salt) ratio, marinates the anchovies in it and then washes them in Sharavati estuarine water an hour or two later. She then spreads the fish on the concrete platform for sun drying. It takes 1-2 days to lose 65-70 percent of its weight. The weight reduces to 30 percent of original weight, which is regarded as optimal for dried anchovies. The raw material decreases from 30-35 kg to 10-12 kg of dried anchovies. She then sells dried anchovies in the wholesale market in Kolaga (a wooden bowl that can hold about 500g of anchovies) for ₹100 to ₹130. Apart from Kolaga, retailers also use Seru, which is a smaller measuring bowl/pail that can hold roughly 300g of anchovies and is sold for ₹100.

Figure . Weights, measurements and prices in the dried anchovies supply chain at Honnavara.

Figure 7 provides a photographic coverage of different stages in dried anchovies processing and the weights and measurements used therein. A photo of the Kolaga and Seru pails, made of wood, are also provided in Figure 7. One Kolaga of dried anchovies contains about 480g of fish, and is sold at ₹125 per Kolaga. One kg of dried anchovies costs about ₹180-220. Thus, again, selling by traditional measurements gives better returns to the seller than modern weight-based pricing.

At Malpe fishing harbor in Udupi, the raw material is purchased as heaps through auctions. Fishers make an estimate of the weight of the heap based on the number of boxes unloaded from the boat to the landing center required to make one heap. Anchovies weigh around 35-40 kgs in each heap. The processed and dried anchovies are sold in kg. In Kundapura, the anchovy is bought through auction process. A basket of wet anchovy weighs 20 to 35 kg. The wet anchovy is usually weighed by a boat crew member or an agent, who then keeps it for auctions. The raw material is processed into dried anchovies and sold in kgs especially in the hinterland of Karnataka.

Weights and measurements in the dried estuarine shrimp supply chain

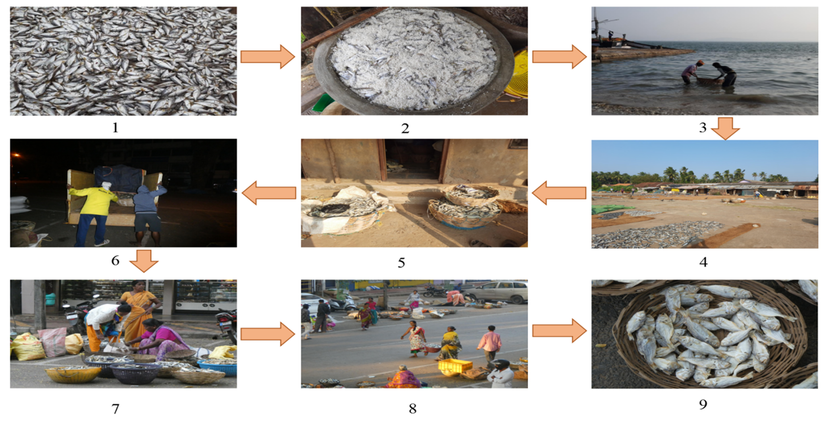

Dried shrimp is another hugely popular delicacy and an important part of the diet especially in Uttara Kannada and Konkan region. As a result, people keep/store it and use it throughout the year in small quantity. Kannada name for shrimp is sigadi and in Tulu it is called yetti. The river Aghanashini flows through Kumata to join the Arabian Sea, forming thousands of hectares of estuarine wetland locally known as Gajani. Farmers sow a type of saline resistant paddy called Kagga in these wetlands at the onset of the southwest monsoon in June. After harvesting the paddy by November, fish/shrimp seeds are allowed to enter into the fields during high tide, and are reared in the inundated fields until harvest. Fish/shrimp are harvested by filtering them when they try to escape during the low tides. Filtering is carried out continuously from October to June by innovatively utilising the bund structures. Larger shrimps are sent to processing factories, while the extremely small shrimps are dried directly on the concrete floor. Dried shrimp is purchased in modest quantities by local (mostly women) vendors and sold in local markets. Women fish traders at Tadadi and Kumta purchase dried shrimp in bigger quantities and sell in the Karwar wholesale market. The harvested and dried estuarine shrimp is sold in kg. The women wholesale vendors who bring it to the Karwar market sell it in traditional measure called Kolaga. And the retailer who buys shrimp by the Kolaga sells it in a smaller unit of measure called the Seru. One Kolaga is about 6 to 7 Seru.

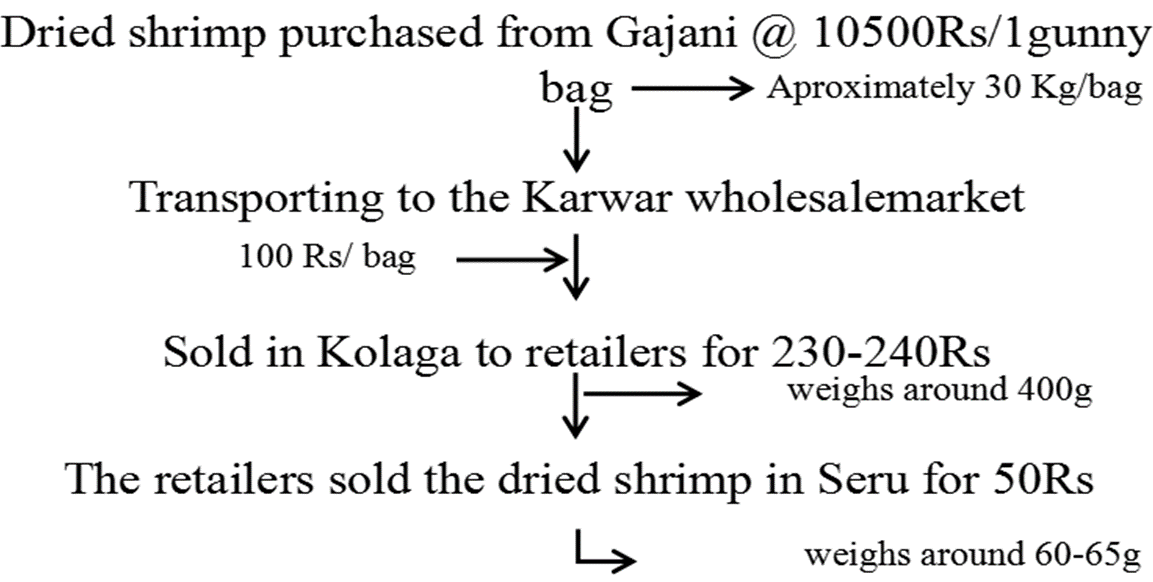

Girija (name changed), a Tadadi-based dried fish processor, described the procurement and selling of dried shrimp and the weights and measurements involved in the process. Table 3 and Figure 8 provide the weights and measurements and the prices along the dried shrimp supply chain. She paid ₹10500 for a whole bag (30 kg) of dried shrimp that she procured from Manikatta Gajani, one of the estuarine wetland areas in Kumata Taluka. She hired a vehicle to transport dried shrimp to the Karwar wholesale market on Sunday morning. She sold the dried shrimp in the wholesale market for ₹230-240 per Kolaga. One Kolaga of dried shrimp weighs approximately 400g. Retailers who bought from her sell the dried shrimp to the final consumers using Seru. A Seru of dried shrimp weighs approximately 60 to 65 grams and sold to the consumers at ₹50.

Figure . Weights, measurements and prices in the dried shrimp supply chain at Tadadi.

Table 3. Weights, measurements and prices along the dried shrimp supply chain at Tadadi.

| Dried shrimp supply chain stage | Weights and measurements used | Amount | ||

| Purchasing of dried shrimp | 30 kg bag | ₹10500 or ₹350/kg | ||

| Transportation cost | ₹100 | ₹100 | ||

| Selling price at Karwar wholesale market | Sold in Kolaga (a pail of 400g) at ₹230-₹240 | ₹580-₹600/kg | ||

| Selling price at Karwar retail market | Sold in Seru (a pail of 60-65g) at ₹50 | ₹770-₹830/kg | ||

Figure 9 gives a photographic representation of the dried shrimp supply chain and the use of weights and measurements. The notes below the figure provide descriptions of the individual photographs.

The dried shrimp trade begins in kgs at the production sites and then switches to the indigenous systems of measurement, i.e., Kolaga and Seru, at the wholesale and retail markets, respectively. Previously, traditional measurement units were employed even while purchasing dried shrimp at the Gajani (upstream market), a practice that vanished over time, with Kolaga/Seru replaced by the standard unit, i.e., kg. However, the indigenous system persists at the downstream levels of the supply chain. Final consumers often buy dried shrimp in smaller quantities. Hence, it is apparent that the traditional measurements system works well for them. One of the reasons is the rapid loss of weight as the moisture in the shrimp declines making it unviable if standard weight units of kg or grams are used. This remains an important reason keeping the indigenous volume-based system viable. As shown in Table 4, selling by the traditional measurements works out better compared to weights-based pricing in terms of profits.

Table . Dried estuarine shrimp measurements and pricing.

| Bowl (Kolaga and Seru) | Price per Kolaga (₹) | Price per kg (₹) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Kolaga (390 g)- in the wholesale market | 240-260 | 600 approx. |

| 1 Seru (65 g)- in the retail market | 50 | 750 approx. |

Findings

The four case studies from Karnataka throw light on various weights and measurements that the dried fish processors navigate along the supply chain. We attempted to understand this supply chain by consciously choosing four different species which are sold to the final consumers in different traditional units of measurements- mackerel in numbers, Lactarius in baskets and heaps, anchovies and small shrimp in Kolaga and Seru. Moisture loss and scale of operation could be some of the prominent reasons for persistence of these traditional systems. Processors have to keep track of changes in quantities brought about by processing as well as the implications of units of measurement. We intended to understand the economic returns to generalize if such traditional systems of measurements are gainful for the processors and traders. Table 5 below shows the price realization to be better in traditional units as compared to standard unit.

Table 5. Price comparisons between traditional and kilogram based dried fish measurements.

| Species | In kg | Price ₹/kg | Dried fish yield in % | Unit of measure | Net weight in kg | Selling price in ₹/kg | Selling price

in ₹/Measure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mackerel | 33 | 60 | 53.9 | Count | 400 | 17.8 | 3560 | 4000 |

| Anchovies | 35 | 50 | 34.3 | Kolaga | 24 | 12 | 2640 | 3120 |

| Lactarius | 30 | 40 | 60 | Basket | 1 | 18 | 2160 | 2400 |

| Shrimp | 30 | 350 | - | Kolaga | - | - | - | - |

The processor has to navigate through the variations in weight while degutting, salting, washing and drying the fish. The change in weight during the processing are presented in Appendix 1. Based on our interview with these dried fish processors, we understood they engage in processing different varieties of fish species based on demand and availability. A typical processor procures different species in certain quantities. A heuristic yet representative quantity of fish processed by a typical processor is provided in Appendix 2. Working capital required for each species varies. We have calculated the approximate working capital required to produce dried mackerel (Appendix 3), anchovy (Appendix 4), and Lactarius (Appendix 5). Considering other costs including fixed capital (Appendix 6), Table 6 below shows that the processors gain nearly three times more using the traditional method of measurement. Thus, the processors and sellers would lose out financially by switching to standard weights and measurements.

Table 6. Returns from dried fish sales, comparison of traditional weights and measurements vs. kilogram.

| Particulars | Price (₹) | |

| 1 | Raw material cost | 1026900 |

| 2 | Total working capital* | 353864 |

| 3 | Total | 1380764 |

| 4 | Revenue by selling in kg | 1770400 |

| 5 | Revenue by selling in traditional method | 2373000 |

| 6 | Gross returns by selling in kg (4)-(3) | 389636 |

| 7 | Fixed cost | 82000 |

| 8 | Net returns by selling in kg (6)-(7) | 307636** |

| 9 | Gross returns by selling using traditional methods (5)-(3) | 992236 |

| 10 | Net returns by selling using traditional methods (9)-(7) | 910236** |

*For details of working capital see appendix tables 3,4, and 5

**These returns do not include the opportunity cost of labor of the processor.

Discussion

In modern market systems with standardized weights and measurements, repeated transactions can lead to convergence in the valuation of products. The prevalence and continuity of traditional systems of measurements may not be just manifestations of resistance to the modern units. When a system of measurements is regularly used over a long period of time, it becomes integrated into the socioeconomic system. Thus, there is an issue of habit formation in the cognitive processes of its users (i.e., buyers and sellers), and hence replacing it with a newer system becomes difficult. Digging deeper, a number of factors could be playing a role in the persistence of these systems in local economies led more often by women. Better economic returns, as identified in this study, is one of the major reasons. However, conventional economics alone cannot explain the continued use of non-standard measurement system, in spite of it not being used in some nodes of the supply chain. This requires probing into the social economy, cultural and other factors that can explain the socially embedded nature of economic transactions. We observed a few of these aspects while collecting information on the weights and measurements in the supply chain and transaction nodes. Traditional transaction systems are prevalent where the food systems are highly localised. Divisibility, need based procurements, trust in the availability of the food items that discourages storage/accumulation are some of the important observed factors associated with the persistence of the traditional measurement systems. Another probable reason for the continued use of traditional measurements by sellers of dried fish in Uttara Kannada could be the different time path of economic development charted by the district, compared to Dakshina Kannada and Udupi that industrialized much earlier, on a larger scale, and at a faster rate. The industrialised regions have moved on to the modern weights and measurements. Would that mean that the traditional weights and measurements would also disappear from Uttara Kannada over a period of time? Probed further, these traditional weights and measurements used in the food supply chain nodes would tell more about the social, ecological and livelihood embeddedness of the local food systems and perhaps suggest a sustainable pathway.

- ↑ Uttara Kannada is also less industrialized, compared to the other two coastal districts of Karnataka. The people of the district have resisted industrialization through several legal and civic struggles in the past. However, the district is most likely to be industrialized over the next decade or so particularly with the new Blue Economy policy of the Government of India.

- ↑ Many species of anchovies and shrimp landed in Karnataka, and those shown in Figure 1 are only representative